As a residential area from approximately 9,000 years ago, Çatalhöyük consists of two mounds located in the east and west sides. It was a settlement area during Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods and carries with it great mysteries and secrets to this today.

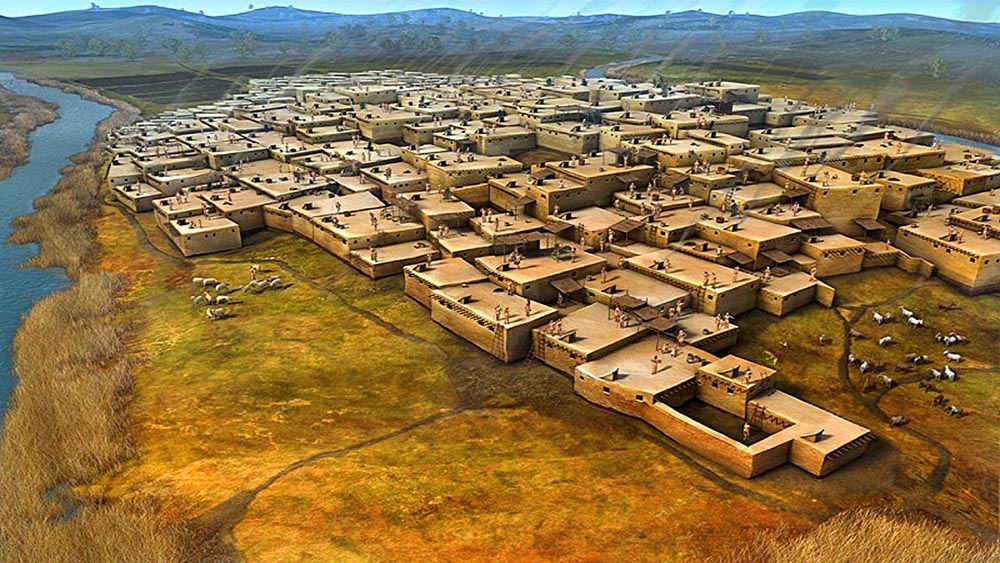

Çatalhöyük is in Konya city, 52 kilometers away from the city center. In particular, traces which belong to settlements during Neolithic Period draw attention. The sheer size of this settlement area, its high population, and their artistic and cultural values make Çatalhöyük extremely appealing. As a result of the research, it is now known that approximately 8,000 people lived in the settlement areas. There is a difference between Çatalhöyük and other known settlement areas of the Neolithic Period. This difference is the fact that folks of the Neolithic Period abandoned their villager status and began an urbanization phase, moving from rural to urban. Regarded as one of the oldest settlement areas in the world, Çatalhöyük is one of the earliest agricultural societies.

The east side of Çatalhöyük has carried the oldest Neolithic Period remnants found so far to this day. Discovered in 1958, excavation of the region initially began in 1961. Excavations made in 1993, and still ongoing, are managed by Cambridge University. Operations made on the main mound are planned to continue through 2018.

Çatalhöyük. (Photo: Turgut Tarhan, Atlas Magazine)

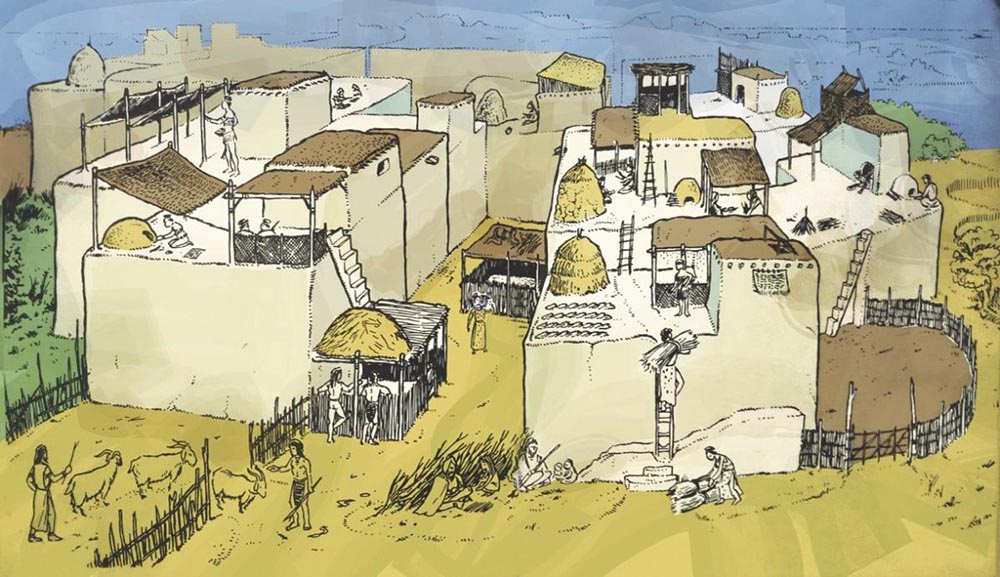

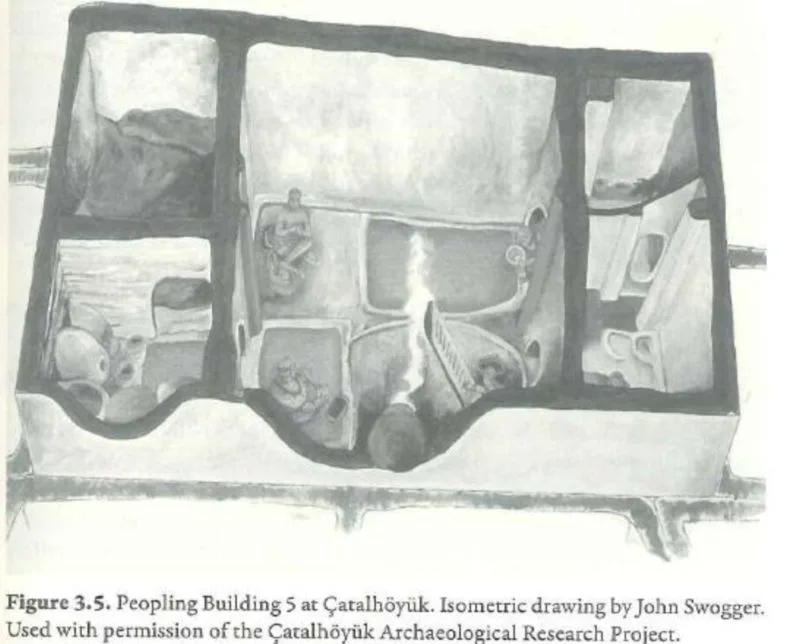

Eighteen neolithic settlement layers were excavated in the East Çatalhöyük area. The architecture alone in this place demonstrates the area’s uniqueness. Gateways, canals, and streets had a significant impact and part to play on this architecture. There was no central palace or temple, nor were there storage rooms in this settlement area. Houses were built next to each other in the area which consisted of only open areas and houses. What resulted were actual neighborhoods. The residents of the area were highly successful at working with wooden materials and with basket-making and they proceeded into pottery making in the later periods. That’s why the earliest made pots were black and badly produced. Other remnants found from this period are mace heads, mirrors, garlic presses, rings and bracelets, adzes, needles, and spoons.

Houses were built next to each other in the area which consisted of only open areas and houses.

Pottery remnants were also found in the West Çatalhöyük area. That’s why it is argued that it was a Chalcolithic Period settlement. In this excavation site, pottery from Hellenistic and Byzantine Periods were also discovered. Buildings in this area were designed with big, rectangular construction plans. The people of the west side made many general pottery pieces and designed some tools such as a hand-mill, scoop, and spoon, and they made jewelry.

Pottery remnants were also found in the West Çatalhöyük area. That is why it is argued that it was a Chalcolithic Period settlement.

It was also found out that people living in Çatalhöyük had an entombment tradition and this line of research unearthed human bones. According to the remains, the dead were buried in the fetal position. Some jewels were put on the dead people before burial. In addition, people buried their relatives under their houses.

Rug patterns, flower designs, and geometric shapes were used on the artistic works of that period. Heads and bull horns were used as accessories in people’s homes. Also discovered among the extant remnants are some boards that depict human and animal figures. Apart from these, another interesting find from this period is the fact that human and animal skulls were buried individually. Researchers emphasize that this indicates skulls were considered valuable financial objects of the era.

Food Culture at Çatalhöyük: Insights from Catherine Hastorf

This article shares insights from Catherine Hastorf’s chapter “The Habitus of Cooking Practices at Neolithic Çatalhöyük – What Was the Place of the Cook?” in the book The Menial Art of Cooking. But first, let’s explore a few general facts about Çatalhöyük:

- Stable Food Practices: Over the course of a thousand years, dietary habits at Çatalhöyük remained remarkably stable. Considering human nature’s tendency to seek novelty, this consistency suggests strong social rules and a culturally conservative community.

- Environmental Setting: The settlement was built in a wetland area along the Çarşamba River. Homes were rebuilt in the same manner repeatedly over centuries, with identical layouts including hearths, ovens, platforms, storage pits, and decorations. This repetition reinforced daily life structures across generations.

- Communal Identity: The sameness in household architecture and burial traditions suggests that individuals were defined more by communal identity than by individuality. The absence of nearby settlements also hints at a preference for close-knit community living.

- Urban vs. Rural Divide: While homes were tightly packed, farmlands extended 15 km away; indicating a clear separation between domestic and agricultural spaces.

- Use and Reuse of Homes: Houses were used for 45–90 years, typically across three generations. Food storage areas were distinct and separate from living spaces, while burials were under raised northern platforms within homes.

- Construction Practices: Walls and floors were regularly replastered. Especially clean and cared-for were the northern burial platforms. Micro-analysis of floor residues revealed food preparation areas; some activities took place on rooftops or outdoors.

- Architecture Reflects Culture: The strong regularity and ritualistic burial practices indicate a community defined by shared traditions and enduring family ties.

Neolithic Diet: What Did They Eat?

Information on diet comes from botanical remains, phytoliths, microresidues, bones of land and aquatic animals, eggshells, organic molecules, and isotopic analysis of human bones. Cooking tools like woven baskets, clay balls, stone tools, and ceramic pots add further insights.

- Balanced Nutrition: Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants had a mixed diet; consuming both plant and animal-based proteins and carbohydrates. All adults ate meat, and food was sourced from both farming and wild foraging. Men and women ate similar diets and performed similar work.

- Starchy Foods: Tooth decay and tartar suggest starchy food consumption. Cavities were present in 46.5% of adult teeth, while 36% had tooth fracture; evidence of frequent consumption of hard foods.

- Preserved Foods: Dried fruits and possibly cured meats were consumed. Dental analysis shows whole grains and nuts were part of the diet. Although grinding stones were found, their limited number suggests many foods were eaten unground.

- Wild Foods: One fecal sample revealed shells of wild pistachios, acorns, and almonds; suggesting people even ate the shells.

- Seasonal Fruits & Roots: While rare, forest fruits and nuts were regularly consumed. Reed rhizomes were widely used. Emmer wheat was the primary grain, and legumes sometimes made up 40% of food sources.

- Occasional Wild Protein: Wild plants, game, eggs, birds, and fish were rare. Most meat came from male sheep and goats. Pork and beef were reserved for feasts or special occasions.

- Minimal Change Over Time: Over the millennium, dietary components changed little; barley disappeared after early periods, rye was added later, and grain usage gradually increased.

- Food Storage: Fruits and nuts were often found in clusters, implying seasonal storage. The remarkable stability of the food culture makes even minor dietary shifts historically significant.

Food Preparation and Storage

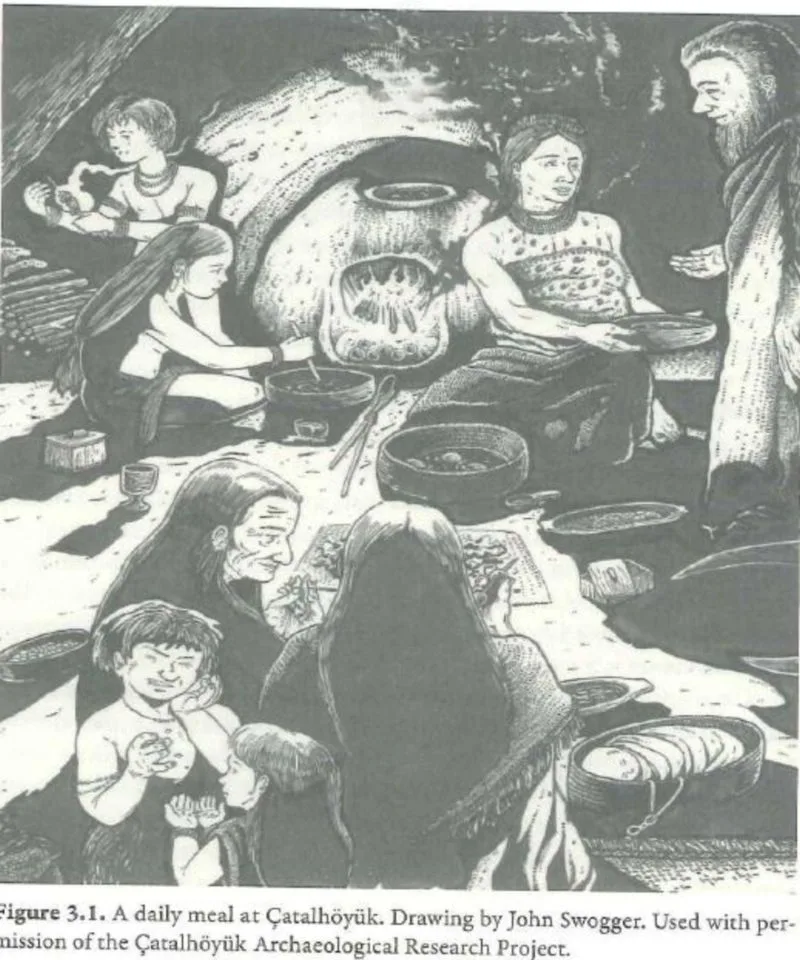

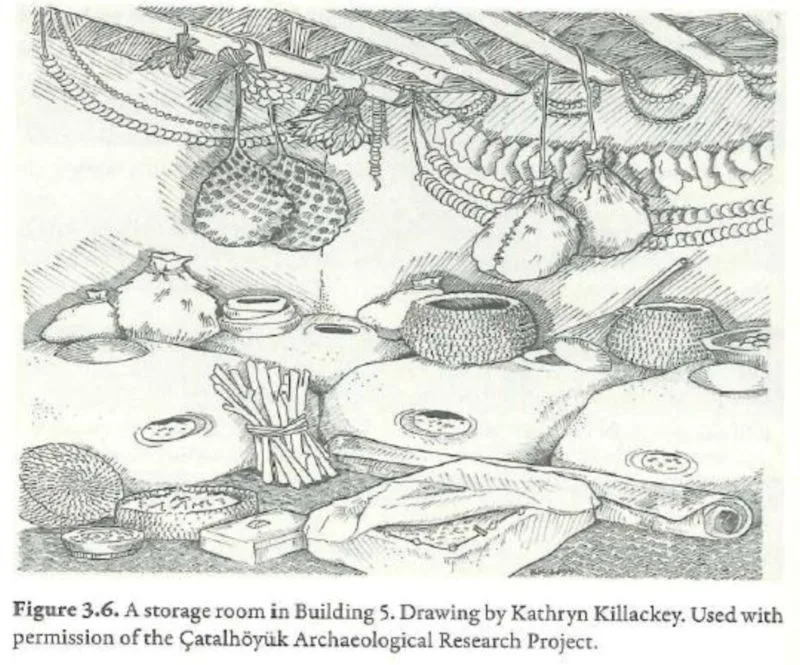

- Storage Vessels: In addition to permanent clay and open containers, woven baskets and bags (with organic residues) were used to store grains, nuts, meat, fat, dairy, and fruit. The frequent discovery of female figurines in seed jars and hearths reveals the deep ties between food and ritual.

- Cooking Techniques: Evidence exists of drying, frying, smoking, pounding, grinding, straining, salting, fermenting, pickling, and cutting. These took place in side rooms or near hearths and ovens.

- Ceramics: Early levels had minimal pottery; mainly for fat storage. Storage relied on organic containers made of leather or reeds. After level VII, pottery vessels were introduced and began to grow in size, enabling boiling, brewing, fermenting, and long-term storage.

- Clay Technology: Clay was always part of Çatalhöyük life; seen in ovens and cooking balls. Cooking vessels came later and allowed for more complex meals, likely reflecting cultural shifts rather than simple practicality.

The Cook and Cooking Spaces

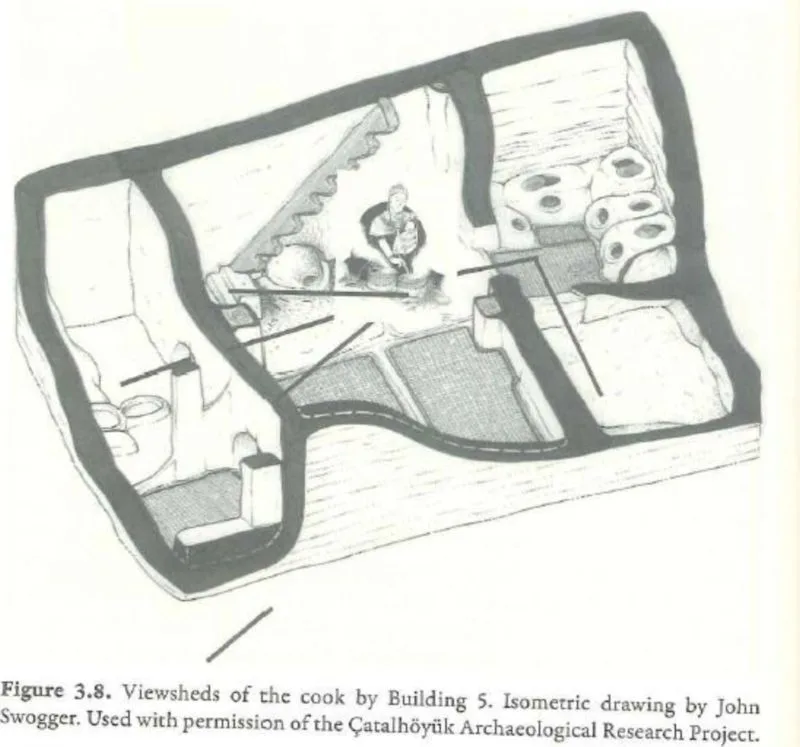

- Where Cooking Happened: Cooking took place both inside and outside homes; in summer on rooftops, and in winter near the oven. Moldy smells in certain rooms and dense organic residues point to food-related activities. Ovens and hearths were also social centers.

- Cooking Installations: Among 250 houses, 90 clay ovens and 160 hearths were found. Ovens were permanent, dome-shaped, and made of fired clay; hearths were smaller and temporary. Over time, ovens grew in size and prominence within homes.

- Cooking Practices: Food preparation involved flatbread baking, sautéing meat and vegetables, boiling porridge and fruit drinks, and roasting grains and fruits.

- Early Cooking Methods: In the beginning, cooking was done using heated clay balls. These were preheated and placed into liquid-filled organic containers, requiring frequent stirring and ball replacement. Similar techniques using stones were found at other sites. It took 600 years for Çatalhöyük to adopt direct-fire cooking.

- Visibility of the Cook: Positioned centrally, the cook could see all rooms and roof access. As ovens grew, the cook’s visibility increased; reflecting their rising social role in family life.

- Who Were the Cooks?: Cooks could be male, female, young, or old. However, many burials near ovens belonged to women, suggesting these were primarily women’s domains. Elderly men and women also spent significant time by the fire. Only the elderly had black carbon traces in their chest cavities, signs of prolonged exposure to indoor smoke. Walls near these zones were stained with soot.

This detailed window into Çatalhöyük’s culinary practices reveals not just what people ate, but how their foodways reflected deep cultural, social, and even spiritual structures. In Çatalhöyük, eating was more than sustenance, it was community, tradition, and ritual.